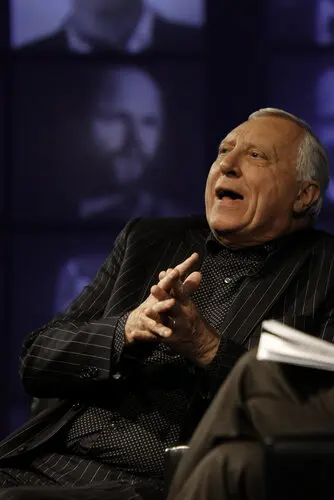

Peter Greenaway, groundbreaking BAFTA-winning British film director, screenwriter and artist explained that “the editor is the king of cinema”.

Greenaway scooped an Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema BAFTA in 2014 for distinctive films like The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover and Prospero’s Books. He told the audience at a special Life in Pictures event that today editors were right at the heart of the filmmaking process.

“Certainly, now in 2016, the king of cinema, the most potent manipulator is the editor,” he said.

“You might have said 30 years ago it was the cameraman. But basically now an editor can do anything with a picture. With the digital revolution you can transmogrify any image into any other image. My great hero Eisenstein was a brilliant film editor, and I think it shows.”

Read the full transcript of Peter Greenaway’s Life in Pictures BAFTA event at Princess Anne Theatre London on 13 April 2016 and explore pictures from the night below: