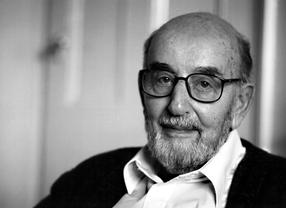

In celebration of DoP Wolfgang Suschitzky's centenary year, Patrick Russell looks back over the life of this inspirational man, whose career in film and photography spans well over seven decades.

Get Suschitzky

© Julia WincklerThe titles begin. Light at the end of a tunnel slowly swallows the black frame with onrushing train-track. Cut to Michael Caine in his seat, pan past his fellow passengers, via warehouses and factories speeding past the train-window. Nine further times will we cut between these scenes: phantom ride, landscape views, Caine, credits and black.

© Julia WincklerThe titles begin. Light at the end of a tunnel slowly swallows the black frame with onrushing train-track. Cut to Michael Caine in his seat, pan past his fellow passengers, via warehouses and factories speeding past the train-window. Nine further times will we cut between these scenes: phantom ride, landscape views, Caine, credits and black.

This iconic opening sequence, from 1971’s Get Carter, forms among other things the junction at the centre of the criss-crossing career of the man directly behind the camera. Knowing northeast England, intimately familiar with industrial Britain, he doubtless feels at home, far from any studio, shooting mute footage of gritty landscapes, but is fluent, too, with the human face, with helping his director expose the truth within the drama, as well finding the drama in documentary images. Director of Photography Wolfgang Suschitzky is, at the time, pushing sixty. Fast-forward to 2012 and he’s still standing.

What is it about DoPs? They may not all be long-lived but there sure is a pattern. Stanley Cortez made it to 91, Henri Alekan to 92, John Alton to 94… Turning to Britain, consider Jack Cardiff, Freddie Young, Ronald Neame, leaving life at 94, 96 and 99 respectively. Christopher Challis died recently, at 93. Ossie Morris remains with us at 96, as does Douglas Slocombe, at 99, and Slocombe's friend and elder: Wolf Suschitzky, known in the business as Su. He turns 100 on 29th August 2012.

The party will be for friends and family, but 19th July sees the Centenary of Su celebrated in public (to this self-effacing centenarian’s slight embarrassment, no doubt). At a special event at BFI Southbank, BAFTA will honour this longstanding, still-active member with a Special Award for Creative Contribution, concluding an evening of tributes from colleagues, evocative extracts (some long-unseen), and thoughts from the man himself.

Anyone with any feeling for the recent past (anyone, that is, not hopelessly lost in shallow worldliness) is prone to a certain star-struck sentimentality when in the presence of people of distinction living amongst us in great old age. Certainly, durability is worth celebrating. In Suschitzky's case, his place at the head not just of two but of three generations of cameramen adds a further exhilarating twist (son Peter, among many illustrious credits, is best-known as David Cronenberg's long-time DoP; grandson Adam has done fine work in features, documentaries and, particularly, TV drama).

Suschitzky personifies the diversity both of the business and of the art of filling the screen.

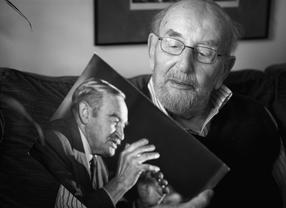

Wolfgang SuschitzkyBut the romance of longevity notwithstanding, Suchitzky’s is a rewarding, singularly instructive career, his centenary a reminder of important truths about filmmaking. 20th century screen history, certainly in Britain, was as much as anything the sum of its sub-plots. Though his camerawork was always excellent, Suschitzky's career wasn’t (as was Cardiff’s, say) studded with certified masterpieces of narrative cinema. Carter is the exception in this respect (and was divisive in its day). Suschitzky instead personifies the diversity both of the business and of the art of filling the screen: classics, cult items, curios; features and shorts; documentary and fiction; cinema and TV; industrial, charity and natural history films; and, last but not least, innumerable commercials (most destined never to be documented). His career, too, makes illuminatingly connects motion with still photography. Suschitzky is renowned as a committed, beguilingly gentle photographer of human and industrial scenes, animal life, occasional distinguished portrait sitters, and the world’s children. There is much to be gained from study (two attractive albums by Austrian publisher Synema making a fine starting point) of the artistic connections between his work in the two media. The practical connections, too: it was film commissions that took Suschitzky to many of the places in Britain and abroad where his best photographs were taken.

Wolfgang SuschitzkyBut the romance of longevity notwithstanding, Suchitzky’s is a rewarding, singularly instructive career, his centenary a reminder of important truths about filmmaking. 20th century screen history, certainly in Britain, was as much as anything the sum of its sub-plots. Though his camerawork was always excellent, Suschitzky's career wasn’t (as was Cardiff’s, say) studded with certified masterpieces of narrative cinema. Carter is the exception in this respect (and was divisive in its day). Suschitzky instead personifies the diversity both of the business and of the art of filling the screen: classics, cult items, curios; features and shorts; documentary and fiction; cinema and TV; industrial, charity and natural history films; and, last but not least, innumerable commercials (most destined never to be documented). His career, too, makes illuminatingly connects motion with still photography. Suschitzky is renowned as a committed, beguilingly gentle photographer of human and industrial scenes, animal life, occasional distinguished portrait sitters, and the world’s children. There is much to be gained from study (two attractive albums by Austrian publisher Synema making a fine starting point) of the artistic connections between his work in the two media. The practical connections, too: it was film commissions that took Suschitzky to many of the places in Britain and abroad where his best photographs were taken.

Wolfgang Suschitzky was born in Vienna in 1912, to a Jewish (non-practising) and socialist (very-much-practising) family. Both facts would likely have lost him his life long ago had he not fetched up in London, via the Netherlands. His sister Edith Tudor-Hart (herself an important documentary photographer) had settled here first. After seventy-seven years in Britain, Wolf retains his distinctive Austrian accent, and left-leaning politics (he for instance regrets the decline of strong trade unionism in Britain’s film and TV industries in the years since his retirement).

© Tony WallisWhile simultaneously pursuing his photographic career, Suschitzky entered the movies in the late 1930s, as a cameraman at Paul Rotha Productions, part of the Documentary Movement whose civic commitment attracted him. In 1944, he was one of the Rotha employees, led by the charismatic Donald Alexander, who departed to form DATA (Documentary and Technicians Alliance), Britain’s first film cooperative. He was an active member for twelve years. Hoping to produce radical documentaries, DATA became best known for quintessential post-war consensus filmmaking: the National Coal Board’s cine-magazine Mining Review (which guaranteed its makers’ exposure to, and deepening affection and respect for, Britain’s coalfield communities).

© Tony WallisWhile simultaneously pursuing his photographic career, Suschitzky entered the movies in the late 1930s, as a cameraman at Paul Rotha Productions, part of the Documentary Movement whose civic commitment attracted him. In 1944, he was one of the Rotha employees, led by the charismatic Donald Alexander, who departed to form DATA (Documentary and Technicians Alliance), Britain’s first film cooperative. He was an active member for twelve years. Hoping to produce radical documentaries, DATA became best known for quintessential post-war consensus filmmaking: the National Coal Board’s cine-magazine Mining Review (which guaranteed its makers’ exposure to, and deepening affection and respect for, Britain’s coalfield communities).

Rotha’s fiction debut was also Suschitzky’s first feature, the unusual Irish tinker drama, No Resting Place (1951). Jack Clayton’s The Bespoke Overcoat (1955) won an Oscar for Best Short, while Wolf’s first foray into TV came via episodes of a Charlie Chan series. Through the next decade, he alternated quirky features, ads and a steady stream of non-fiction shorts (increasingly many in glossy colour, directed by established, but underrated, documentarists such as Sarah Erulkar, Peter de Normanville and Paul Dickson). He also worked with rising talent: for Hugh Hudson, he shot several corporate films and many commercials. From the late 1960s, Suschitzky was increasingly in demand as a features DoP, though he never abandoned his non-fiction origins, still photographing industrial training films as late as the 1980s.

Suschitzky has been retired since 1987. This lifelong filmgoer remains a dedicated one, regularly spotted at screenings. Usually with partner Heather Anthony, sometimes solo, he comes by bus, takes the stairs, often ends his evening with some red wine. Wolf says: ‘Art can be produced with any medium… but only in the hands of an artist. Unfortunately there are not many of those about. I certainly don’t claim to be an artist. I am content, if I am considered a craftsman.’ It’s hard to believe that so secure a sense of self, founded on professional pride, personal humility, and patience, is not part of the secret of Su, perhaps of cinematographers in general.

Words by Patrick Russell.