In January, BAFTA hosted two special Tribute events in honour of the outstanding work of cinematographer Roger Pratt and Film4 deputy director Sue Bruce-Smith, celebrating their wonderful contribution to cinema. Words by Mike Goodridge and Toby Weidmann

Every year, BAFTA hosts Tribute events to celebrate the work of exceptional British practitioners who have not previously won a BAFTA award. In January 2019, two such events were held to recognise the outstanding contribution to the film industry of Sue Bruce-Smith and Roger Pratt. Both events saw the presentation of a BAFTA Special Award, by BAFTA trustee and co-president of Cornerstone Films, Alison Thompson, to Bruce-Smith, and actor Michael Palin to Pratt.

With an ongoing career spanning more than 30 years across finance, production, marketing, distribution and international sales, Bruce-Smith has been integral to the release of some of the UK’s most successful films, including This Is England (2006), Slumdog Millionaire (2008), 12 Years a Slave (2013) and, most recently, The Favourite (2018).

Director of photography Roger Pratt’s memorable work covers an impressive repertoire of films, including Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986), Richard Attenborough’s Shadowlands (1993) and Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994). He earned two BAFTA nominations, for Chocolat (2000) and The End of the Affair (1999), for the latter he was also Oscar-nominated.

Sue Bruce-Smith

Photo Credit: Nikki Wills

There are very few people as rooted at the epicentre of British cinema as Bruce-Smith. Perhaps none. Since the mid-1980s, she has held numerous roles, developing one of the most respected reputations in the business. She has always preferred to stay in the background, determined to help the various projects and filmmakers she has been involved with but never to impose her will.

Like many industry stalwarts, Bruce-Smith started her career (in 1985) at Palace Pictures, the rule-breaking independent production company/distributor, which threw a grenade at the established way of releasing movies. Working for current Film4 director, Daniel Battsek, she was initially print and bookings manager and then marketing and distribution manager. “I was incredibly lucky to land at Palace,” she recalls. “Everyone was hugely inventive and questioning of the orthodoxy, which made it a dynamic and pretty anarchic environment filled with highly creative people... Daniel left no stone unturned in our marketing campaigns.” She cites such classics as The Company of Wolves (1984), Letter to Brezhnev (1985), Hairspray and High Hopes (both 1988).

But in 1989, she changed tack, taking the role of head of international sales for the British Film Institute’s production division, where she worked on The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Last of England (1987), among others.

In 1993, she moved to BBC Worldwide, determining its investment strategy in feature film production and establishing a worldwide theatrical life for such films as Mrs Brown (1997), The Snapper (1993) and Persuasion (1995). She then spent four years at Film4’s international sales department, but left in 2001 to live in Dublin with her family. Here, she joined independent production outfit Little Bird.

“Throw yourself into the work, ask plenty of questions and make sure you work with people who inspire you and bring out the best in you.” – Sue Bruce-Smith

In 2004, she got a call from Tessa Ross, who was spearheading a new incarnation of Film4, asking her to rejoin the team as head of commercial development. It heralded a golden era at Film4, thanks to the creative genius of Ross and the calibre of the creative teams she put in place. After Battsek joined Film4, he promoted Bruce-Smith to deputy director in 2017. She is more passionate than ever about the company’s mandate of making bold and resonant cinema in a period of such immense change for the industry.

“Don’t be afraid of embarking on something new,” she advises. “Throw yourself into the work, ask plenty of questions and make sure you work with people who both inspire you and bring out the best in you.”

As for her BAFTA tribute, she smiles: “I’m hugely honoured. It is lovely and also surprising to be acknowledged, having spent much of my career trying not to be noticed!” MG

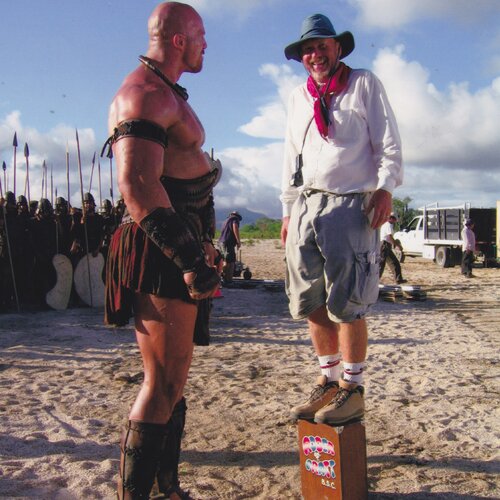

Roger Pratt

Photo Credit: The Pratt Family

The work of cinematographer Roger Pratt BSC is deceptive. An expert of both light and shadow, Pratt’s work displays the sort of old school filmmaking that wouldn’t seem out of place in the heyday of film noir, using light to convey mood and to pick out objects via tonal separation. And yet he also has a talent for sumptuous colour, perhaps best illustrated by his two ‘foodie’ features, Chocolat and Jadoo (2014). Has food ever looked so delicious and seductive on film before? The balance of rich colours and deep shadows also mark his exceptional cinematography on two Harry Potter excursions, The Chamber of Secrets (2002) and The Goblet of Fire (2005), as well as the epic Troy (2004).

Born in Leicester in 1947 and a graduate of the London Film School, Pratt earned his union card working at a film laboratory before moving to Chippenham Films, which brought him into contact with the Monty Python team (and Terry Gilliam in particular). He says he followed the traditional route to cinematographer, serving as camera loader, focus puller and so on before debuting as director of photography on Roger Christian’s The Sender (1982). Christian told Screen International at the time, “Roger’s lighting will launch him to the top of the ladder,” and he wasn’t wrong; Pratt was soon landing bigger gigs, including three with Gilliam (Brazil; The Fisher King, 1991; Twelve Monkeys, 1995), four with Lord Richard Attenborough (Shadowlands; In Love and War, 1996; Grey Owl, 1999; Closing the Ring, 2007) and two with Mike Leigh (Meantime, 1983; High Hopes, 1988), across his 30-plus films.

“I look at myself as a technician… Photographs, they’re really just chemicals in labs, aren’t they? But they turn into live things.” – Roger Pratt

From jaw-dropping gothic visuals to epic vistas and subtle character plays, Pratt’s incredible filmography demonstrates an enviable mix of the classic with the contemporary. But for Pratt, the art of cinematography is just as much about the practical as the artistic. “People do have the most flowery language to talk about cinematography, the art of it,” he told The New Yorker. “For me, there are many problems on a film that have nothing to do with theories of colour or highfalutin aesthetics. Because my job is concerned with big lumps of lights and metal cameras and laboratories, it’s something that makes half of me very pragmatic; it’s the opposite of artistic. I look at myself as a technician… Photography relies on science… Photographs, they’re really just chemicals in labs, aren’t they? Lights on paper. Images in silver halide. Celluloid. But they turn into live things.”

Pratt’s cinematography does and will live long in the memory of all who see it. TW

The brochure for Sue Bruce-Smith’s Tribute can be found here.

The brochure for Roger Pratt’s Tribute can be found here.